Support us from £3/month

We deal with almost 1000 cases a year assisting communities, groups and individuals in protecting their local spaces and paths in all parts of England and Wales. Can you help us by joining as a member?

This year we celebrate the seventieth anniversary of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act 1949. Our general secretary Kate Ashbrook, explains what it achieved.

This is not just a Bill. It is a people’s charter—a people’s charter for the open air, for the hikers and the ramblers, for everyone who lives to get out into the open air and enjoy the countryside.

So concluded Lewis Silkin, Minister of Town and Country Planning, as he moved the second reading of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Bill on 31 March 1949 (column 1493).

So concluded Lewis Silkin, Minister of Town and Country Planning, as he moved the second reading of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Bill on 31 March 1949 (column 1493).

These are uplifting words, which capture the spirit of that post-war period. The act, which received royal assent on 16 December 1949, was an extremely important start in protecting our most treasured landscapes and recording public paths. Unfortunately, though, Silkin’s words proved rather too optimistic, for the act fell short of the hopes and expectations of conservationists and outdoor activists. These included the Standing Committee on National Parks (predecessor of the Campaign for National Parks), the Council for the Preservation of Rural England (now the Campaign to Protect Rural England), the Ramblers, Youth Hostels Association and ourselves.

But the act did make a significant different and many of its provisions endure to this day.

Measures

The act introduced a wide range of measures.

- It established the National Parks Commission (predecessor of Natural England) with duties which included the designation of national parks (section 2).

- It created the mechanism for designating national parks. These were to be extensive tracts of open country in England and Wales, areas of natural beauty with opportunities for open-air recreation (section 5).

- It introduced the concept of nature reserves (section 15) and sites of special scientific interest (section 23).

- It required the production of definitive maps of public rights of way and set out how this should be done (sections 27-38). This was vitally important: until we had definitive maps you had to prove that the route was a public highway before you could persuade an authority to act against an obstruction.

- It contained provisions for the creation, diversion and closure of public rights of way (sections 39-45).

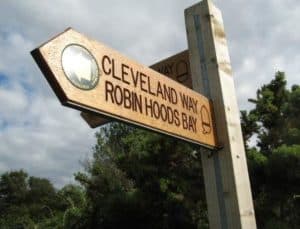

- It empowered the National Parks Commission to recommend to the minister the creation of long-distance routes (now national trails) (sections 51-55) with powers for a highway authority to provide and operate a ferry where the route required one (section 53).

- It introduced a criminal offence of displaying a misleading notice on a definitive path (section 57).

- It defined ‘open country’ as land consisting wholly or predominantly of ‘mountain, moor, heath, down, cliff or foreshore (including any bank, barrier, dune, beach, flat or other land adjacent to the foreshore)’ (section 59).

- It defined ‘excepted land’ (eg agricultural land other than rough grazing, land covered by buildings, parks, gardens or pleasure grounds, quarries, land which already had rights of access) (section 60).

- It required every local planning authority, within two years of commencement of the act, to review its area and ascertain what land there was which met the definition of open country and to consider what action should be taken, whether by access agreement or order, to secure access by the public for open-air recreation there (section 61).

Dunkery Beacon on Exmoor is open country but legal access there was not achieved until the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000

- After completing the survey, the authority must either take the necessary action or forward to the minister a statement that no action was necessary and publish a notice setting out the contents of the statement and inviting representations. The minister could then call a local inquiry or afford those making representations the opportunity of being heard (section 62).

- Within one year of the completion of the review the authority must, unless it had already submitted a statement, prepare and forward to the minister a map showing the approximate extent of the land which was defined as open country and explaining what action had been taken to enable the public to have access to that land, and publish a notice that the map had been prepared and where it may be seen (section 63).

- A local planning authority might, with the approval of the minister, make an access agreement on open country (section 64) or, where an access agreement could not be achieved, an access order (section 65). There were also provisions for securing the means of access to access land (sections 67-68).

- The National Parks Commission also had powers to designate areas of outstanding natural beauty (section 87) although the AONBs were not defined in the act, merely being referred to as ‘any area in England or Wales, not being in a national park, which appears to [the commission] to be of such outstanding natural beauty that it is desirable that the provisions of this act relating to such areas should apply thereto …’.

Worm’s Head at Rhossili in the Gower Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. This was the first AONB, designated in 1956.

Disappointments

There were at least two main disappointments in the act.

One was that the national park committees were spelt out as being independent of the local authorities. Those who promoted the act had envisaged independent boards with a full-time planning officer, and the parks administered as single geographical units regardless of their distribution across county council boundaries.

The first two parks, the Peak District and the Lake District, were established as independent joint boards as the act had intended. The remaining eight (Snowdonia, Dartmoor, the Pembrokeshire Coast, the North York Moors, the Yorkshire Dales, Exmoor, Northumberland and the Brecon Beacons) were established after Silkin had moved to housing and local government and was no longer involved. They were advisory committees to their county councils, relying on the councils for funding and their permission to take action. It was not until the Environment Act 1995 that the parks became truly independent.

The other disappointment was that, instead of creating a public right to roam on open country, the act merely made provision for access agreements or orders. Few were negotiated despite there being acres of open country where access was denied. The requirement for local planning authorities to carry out a survey of open country and determine how to achieve public access there was widely ignored, and it was never followed up. So the ‘access to open country’ provisions of the act were futile.

Milestone

But we did get national parks, AONBs, long-distance paths and definitive maps of rights of way, and the act provided the foundation for much that followed, including the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 and the coastal-access provisions of the Marine and Coastal Access Act 2009.

The 70th anniversary of the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act is a great milestone.