Support us from £3/month

We deal with almost 1000 cases a year assisting communities, groups and individuals in protecting their local spaces and paths in all parts of England and Wales. Can you help us by joining as a member?

In July our general secretary, Kate Ashbrook, went to the biennial conference of the International Association for the Study of the Commons (IASC) in Utrecht in the Netherlands. Here she describes some of her experiences.

This was the 16th biennial, global conference of the IASC, and my fifth. It was organised by the University of Utrecht and held in its fine buildings in the heart of the town.

I am particularly keen to fly the flag for practitioners (ie campaigners). For some time there has been a divide between researchers and practitioners in the IASC but things are changing. At the 2013 conference in Japan the society was presented with the first Elinor Ostrom Award for practitioners. At the 2015 conference in Canada practitioners, including the First Nations, were invited to participate.

Lanyards

For the Utrecht conference practitioners had been encouraged to submit ideas for practitioners’ labs. Activists had been invited from the Netherlands with the result that, of 700 people attending, 150 were practitioners. When we registered on arrival we had to choose the colour of our lanyard, blue for practitioners and green for academics—though many considered they were both.

Both researcher and practitioner: Ruth Meinzen Dick from the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) in the USA and Jagdeesh Rao from the Foundation from Ecological Security in India

The question of what IASC should do for practitioners and for researchers engaged in ‘active research’ was debated a few times. It came up at the members’ meeting where I urged practitioners to work together to decide what they want from IASC, and to be prepared to put in as well as take out. It also came up in the various practitioners’ laboratories, and in the final policy session of the conference. The young scholars had met the night before and one of them presented their conclusions which included: ‘to explore and make more visible the connection between research and social impact’. This was very encouraging.

Practitioners’ lab

I organised a practitioners’ lab called ‘Defending land rights: exploring the solutions to current issues’. Despite being held on the last morning it was well attended. It was chaired by John Powell, president of the IASC, and we had contributors from Peru, India, Mexico, USA and the Netherlands (some with an international or regional remit). Chris Short (for the Foundation for Common Land) and I spoke for the UK. We only had 90 minutes for the presentations and discussion, which was not enough.

Elinor Ostrom Award 2017

Elinor (Lin) Ostrom, who died in 2012, was an international commons champion and Nobel prizewinner. The Elinor Ostrom Award was established in her memory. This year the award for practitioners went to the Asociación Forestal de Soria and was received by Pedro Agustín Medrano. It has done fine work rescuing the forest commons in the province of Soria, north-east of Madrid in Spain. Pedro said that, since he posted the story about the award on the association’s website, he had received over 60,000 ‘likes’—an enviable response.

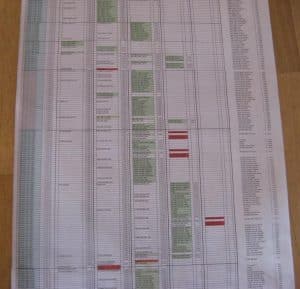

Pedro had with him an impressive roll of paper on which were listed all those who had rights on the commons in one community, with the first generation in the left-hand column, and successive generations in the columns on the right.

The roll itself extended for a whole room. It was easy to see how abandonment had led to fewer people on the commons in the current generation.

It is an emotive document, and one which generates family stories; Pedro explained how the children were fascinated by it and wanted to learn about their predecessors.

Utrecht the city

The city is lovely, and we were in the heart of it. The landmark is the Dom tower, which was originally part of the Domskerk, started in 1321 and completed in 1383.

The nave of the church was destroyed by a tornado in 1684 and, believing this was an act of god, the people decided that they should not rebuild it. Later they removed the damaged portion of the church, and the church and tower have remained separate. A wall hanging shows how the church might have looked.

The opening ceremony was in the Domkerk and was immensely impressive.

Many of the sessions were held in historic university buildings such as the Academiegebouw.

The senate room had portraits of the university’s rectors (almost entirely men).

The town itself is surrounded by and crossed by canals, one of which is the former bed of the River Rhine. There are many green spaces, linear ones besides the canals and parks. Cyclists rule and it was not always clear which were the cycle lanes, it was quite alarming trying to walk in the city centre.

There is plenty of interesting architecture. For instance, my accommodation was close to the Reitveld Schröder House, designed by Gerrit Reitveld in 1924 on the principles of De Stijl (Dutch for ‘the style’). Reitveld built the dwelling for Mrs Truus Schröder-Schräder and her three children. She asked for the house to be designed preferably without walls. It is now a World Heritage Site.

Field trip

As usual, the penultimate day was one of field trips. I went on a visit entitled ‘Keeping the past, building the future’ in the Veluwe area of the Netherlands. First, we went to Ede, a town which is about 20 miles east of Utrecht. We looked at the town itself and then visited neighbouring heathland, a rare habitat in the Netherlands, which is being managed to maintain it as such, with a native breed of sheep, Veluws Heideschaap.

The project leader, Marcel van Silfhout, explained the importance of not allowing the common to become too nutrient rich (familiar stuff, the same issues arise on our heathland commons).

We walked around the boundaries of the old commons, and historian Gerrit Breman explained the history.

We walked paths which had been negotiated by Klompenpaden and were marked with a pair of clogs (but there is also a tradition of open access where it will cause no damage or encroach on property).

We ended at the Doesburger Molen (windmill), the oldest wooden windmill in the Netherlands, with a central oak pillar dating from about 1625.

There is more information about the conference on Kate’s Campaignerkate blog under this tab.