Support us from £3/month

We deal with almost 1000 cases a year assisting communities, groups and individuals in protecting their local spaces and paths in all parts of England and Wales. Can you help us by joining as a member?

This is a year of anniversaries to celebrate in the contests over open spaces around London; 150 years ago, and after long local struggles in each case, legislation was passed preserving Hampstead Heath and Wandsworth Common from development, campaigns in which the Commons Preservation Society (CPS, and the forerunner of the Open Spaces Society) played a prominent role.

Villages were becoming suburbs. Leytonstone c.1870. Credit LB of Waltham Forest Vestry House Museum.

Another key moment in the struggle to save London’s green spaces also took place 150 years ago this year. On 8 July 1871, thousands of east Londoners gathered on Wanstead Flats, the southern boundary of Epping Forest. They were there to protest against the fencing off of a large section of the Flats by the agents of Lord Cowley, major landowner in the southern forest. Like other local landowners Cowley was cashing in on the rising value of land near London. Commerce and industry were driving a huge expansion of the city, and villages on London’s fringe were being transformed into bustling suburbs.

This unprecedented growth was a mixed blessing for Londoners. The new suburbs provided affordable housing for many workers – it wasn’t just the affluent middle classes who were the new residents of the growing outer London districts. But London’s spread was also swallowing up the green spaces which Londoners had for centuries been able to enjoy. By mid-century even the once-remote Epping Forest, east Londoners’ time-honoured playground, was under threat.

That is why, by the summer of 1871, the enclosures on Wanstead Flats were a watershed moment. The east London branch of the CPS had been campaigning for several years against the closing off of Epping Forest, and now took up the fight against this latest incursion. Meanwhile east Londoners had gained another powerful ally. The City of London corporation, sensing the public mood, had sided with the popular cause. Using their position as Epping Forest commoners, with the right to graze cattle across the forest, they warned Lord Cowley against infringing this right with his fences.

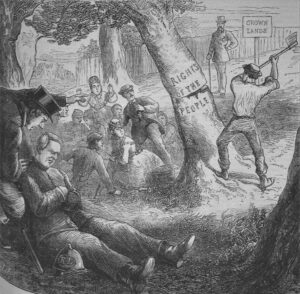

Newspaper cartoon ‘Epping Forest in Danger’ July 1871. Credit Essex Field Club

While the City of London threatened legal action, campaigners called a mass demonstration on Wanstead Flats for 8 July 1871, and thousands descended on Wanstead Flats. By this stage the leaders were increasingly nervous about the Pandora’s Box they had opened, and posters appeared warning against damaging the cause by destroying the fences. The meeting was moved to the grounds of a local house. This was not at all to the crowd’s liking, and amidst a storm of booing the wagon on which the speakers stood was manhandled onto the Flats.

A strong police presence seemed to be enough to keep order, and after appeals not to break the law the leaders left, as did the police. Hours later a single fence rail was broken, and within minutes a huge crowd was laying waste to hundreds of yards of fencing. The police, hastily recalled, managed just one arrest.

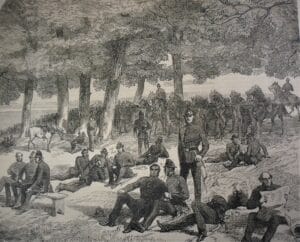

Police on Wanstead Flats July 1871. Credit Essex Field Club

The press by and large condemned the destruction of the fences, though some pointed out that the action grew out of frustration at the failure of the government to protect open spaces from rapacious landowners. Indeed, within a month parliament had enacted the first of a series of Acts to protect the forest.

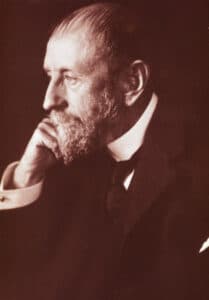

In the next decade parliamentary and legal action played out amidst vociferous public protest. A new campaigning group, the Forest Fund, organised petitions, lobbied local MPs and held numerous public meetings to keep the ‘Epping Forest Question’ alive. Meanwhile, the City of London had brought a legal case against the Lords of Manors in Epping Forest, claiming their fences were infringing commoners’ rights to graze cattle across the whole forest. This technical argument was the largely the work of the CPS solicitor, the indefatigable Robert Hunter, later a founder of the National Trust.

The successful conclusion of this case led to the City of London taking on the management of the forest under the 1878 Epping Forest Act. This was the last of the Epping Forest Acts, and it was revolutionary. It was the first legal declaration of the right of the public at large to use an open space in Britain for leisure. This had implications not just for Epping Forest, but for other threatened open spaces across the country. It is hard to argue with the conclusion of the great ecologist and historian Oliver Rackham that ‘the modern conservation movement began with the campaign for Epping Forest’.

Sir Robert Hunter, a solicitor and founder of the National Trust 1844-1913. Credit National Trust

Yet the role played by ordinary Londoners in this campaign has been forgotten or ignored by history. The focus has been on the efforts of elite campaigners to save open spaces such as Epping Forest, which tells only part of the story. It misses out the grass-roots activism of working class Londoners, whose popular protests played a decisive role in the defence of their green spaces.

The sheer number and determination of the crowd on Wanstead Flats 150 years ago created a groundswell of protest that pressured government into challenging landowners’ rights to enclose land and exclude the public. This and other campaigns contributed significantly to what has become the modern-day ‘right to roam’.

The story of 150 years ago is also today’s story, as the struggles for open spaces continue, all too often against the very public bodies who should be their guardians. Indeed a warning from history is contained in a leaflet issued by a (successful) 1946 campaign against an attempt to build housing on Wanstead Flats by a local council. ‘Once done’ it said, ‘it can never be undone, and history will condemn the folly of those who allowed it to happen’.

Mark Gorman