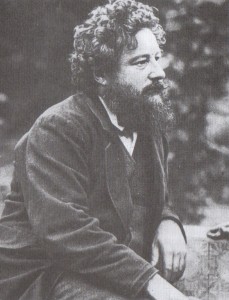

William Morris – open spaces champion

Article originally published in Open Space, summer 2002

Martin Haggerty, newsletter editor for the William Morris Society, explains why that organisation has joined the Open Spaces Society.

William Morris (1834-96) is best known as an artist-designer: his textile and wallpaper patterns, such as ‘Willow’ (1874), ‘Snakeshead’ (1876) and ‘Medway’ (1885), which were innovative in the late nineteenth century, have achieved classic status and remain popular today. He also designed carpets, tapestries, furniture and much else besides. Essentially a practical man, Morris was also a versatile craftsperson, able to insist that Morris & Co would produce nothing that he himself could not make.

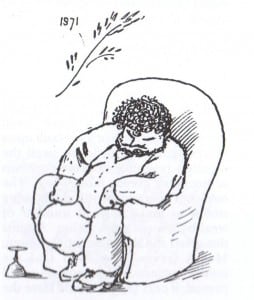

“Home again” ‘William Morris sitting bored in an armchair’ Caricature by Edward Burne-Jones after Morris’s return from Iceland, 1873

Prolific

Though remarkably successful—both artistically and commercially—in this field, Morris was more famous in his lifetime as a writer: a prolific poet whose works include The Earthly Paradise (1868-70) and Poems by the Way (1891), and a prose-writer in romances such as The Wood beyond the World (1894) and the utopian fantasy News from Nowhere (1891), as well as a vast quantity of translations, essays and miscellaneous journalism.

In 1883, he declared himself a socialist and thereafter was an extremely active propagandist for that cause, as a public speaker and a pamphleteer and as the founder-editor of a radical political journal, Justice, which was succeeded by Commonweal.

Morris’s contribution to the conservation movement in its infancy was considerable, and his legacy in this, as in so much else, is enduring. Morris founded the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) in 1877; celebrating its 125th anniversary this year, the SPAB still uses the Manifesto written by Morris and the logo which he designed.

Campaigner

His substantial work as a campaigner for the English countryside is much less well known; and especially his involvement with the Commons Preservation Society (CPS) has so far received little recognition or study. I hope that this article will establish a case for Morris to be regarded as an important figure in the history of the CPS and thus of the Open Spaces Society which evolved from it.

Morris regarded the countryside essentially as a human environment, as a landscape created by people’s physical and spiritual needs. Its beauty, in Morris’s view, stems largely from its necessarily careful management through history, and its continuance is dependent on this close relationship. His inspiring essay Under an Elm-Tree; or Thoughts in the Countryside (1889) repeatedly refers to the ancient white horse cut into the Berkshire Downs at Uffington, suggesting that this landscape expresses a historical struggle and persisting hope for ‘peace and loveliness’, against the dark forces of oppression, those of invading Danes through to ‘capitalist robbers this time’.

Though Morris was a pioneer of ecology, as any reader of News from Nowhere must admit, he did not feel moved to support campaigns to protect wildlife, such as that of the Society for the Protection of Birds, formed in 1889. Instead, he became involved in the Kyrle Society, founded in 1875 to improve working-class housing and the wider environment, and the Commons Preservation Society, founded ten years earlier.

In The Prospects of Architecture in Civilisation (1881), Morris said, ‘I ask your earnest support for such associations as the Kyrle and the Commons Preservation Societies’.

Epping Forest

The CPS had already, in 1874, secured a landmark victory by preventing the enclosure and emparkment of Epping Forest, which Morris claimed to have known ‘yard by yard’ by his childhood wanderings there, and it may have been this campaign which attracted him to this society. Morris devoted a paragraph in News from Nowhere to recounting the continual threats to Epping Forest which concerned him so much.

I have been able to ascertain that Morris attended at least three meetings of the CPS: on 4 August 1881, 25 June 1883 (its AGM) and again some time in early April 1884. He wrote a report of the last of these in Justice (I:13, 12 April 1884), where he took issue with ‘a clever speaker’—possibly the Gladstonian Liberal MP William Harcourt—who had argued that the continuing expansion of London was inevitable, and ‘those present accepted that assumption complacently, as I think people usually do’.

‘William Morris climbing a mountain in Iceland’, caricature by Edward Burne-Jones

Far otherwise with Morris, who was implacably opposed to the whole capitalist system and advocated revolution against it. He regarded the work of bodies such as the CPS not as a palliative against the ugliness and squalor brought by industrialism and an oppressive socio-political system, but as a token of what he and some other people desired in their place; ‘in short the giving back to our country of the natural beauty of the earth, which we are so ashamed of having taken away from it’; an alternative vision of our world.

As he stated in Art, Wealth and Riches (1883): ‘All who assert public rights against private greed are helping us; every foil given to common-stealers, or railway-Philistines, or smoke-nuisance-breeders, is a victory scored to us’. In Art and Socialism (1884), Morris lamented that, in contemporary Britain, ‘the leaders and the led are incapable of saving so much as half a dozen commons from the grasp of inexorable Commerce’; presumably environmental and land-rights campaigners were not counted among ‘the led’.

Land grabber

Also in 1884, in an editorial in Justice, Morris complained that ‘the grip of the land grabber is over us all; and commons and heaths of unmatched beauty and wildness have been enclosed for farmers or jerry-built upon by speculators in order to swell the illgotten revenues of some covetous aristocrat or greedy money-bag’. The land, our common birthright, is being stolen to make a small number of wealthy people even richer. Against that greed and short-term opportunism, Morris fervently believed that the nobler instincts of humankind could prevail, if only people would have the courage to assert them.

Morris constantly appeals to what is best in human nature, identifying the real alternatives to the prevailing values of his age and ours: useful work instead of useless toil, production for use rather than waste, contribution instead of consumption, creativity instead of productivity, genuine reward in our work instead of mere earnings for it, recreation rather than respite, quality of life instead of standard of living.

Perhaps that part of Morris’s vision most relevant to the aims of the CPS and those of the Open Spaces Society today can be found in Art Under Plutocracy (1883), one of his earliest socialist lectures, where he pleads:

to take some pains to keep the meadows and tillage as pleasant as reasonable use will allow them to be; to allow peaceable citizens freedom to wander where they will, so they do no hurt to garden or cornfield; nay, even to leave here and there some piece of waste or mountain sacredly free from fence or tillage as a memory of man’s ruder struggles with nature in his earlier days: is it too much to ask civilization to be so far thoughtful of man’s pleasure and rest, and to help so far as this her children to whom she has most often set such heavy tasks of grinding labour? Surely not an unreasonable asking.

Here we have Morris advocating what we now call good stewardship of the land, freedom to roam and the preservation of wilderness, and he clearly recognises the value of the countryside for recreation as well as agricultural production. The Open Spaces Society is doing excellent work to realise these ideals, so it deserves the support of all Morrisians.

Committee

In a 1990 lecture to the William Morris Society, Professor Paul Thompson stated that Morris was active in the CPS as a committee member between 1876 and 1886, and that he helped to sort out the CPS’s troubled accounts in the financial year 1880-81. One must suppose that the archived records of the CPS, particularly the minutes of meetings and any surviving correspondence between its committee members, hold a wealth of information about Morris’s work with the CPS, which will illuminate this hitherto obscure aspect of his life and work. It would be a superb subject for a postgraduate student to research.

In the meantime, if anyone is able to find out the approximate extent of these records and how much Morris features in them, our society would be delighted to know about it. I believe that I have already, in this article, shared all of our present knowledge of Morris as a member of the CPS.

The William Morris Society (WMS) has recently joined the Open Spaces Society on a reciprocal basis. This action reflects our committee’s wish for the WMS to encourage the causes which William Morris himself championed. We are also very pleased to welcome the OSS as a member of our society and hope we shall mutually benefit from this fellowship. In A Dream of John Ball (1888), Morris rightly observed that ‘fellowship is life’.

For more information about the William Morris Society, please visit the William Morris Society website.

Receive the latest news to your inbox

Sign up to our monthly eZine to stay up to date with news, views, and more from the Open Spaces Society. Signing up takes less than two minutes.